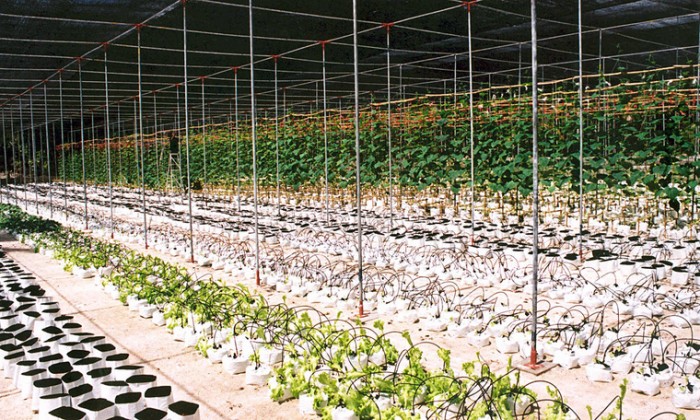

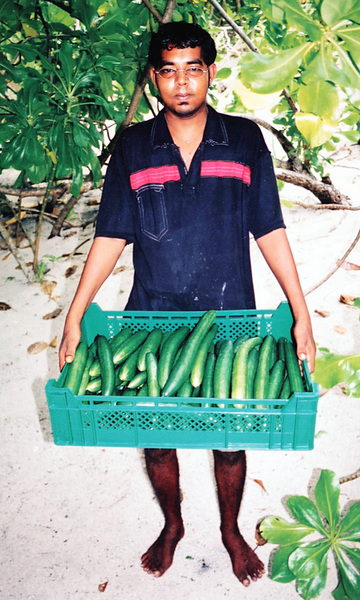

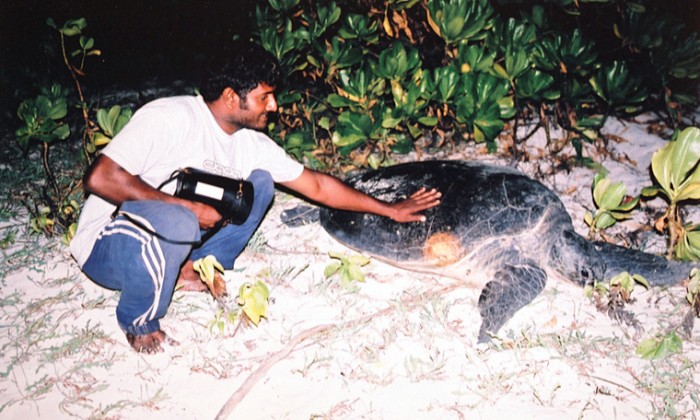

Images of life at the vegetable farm in Maldives 2002-04 including the construction & production process.

Rasheed Araeen (b. 1935 Pakistan) is a London based artist and founding editor of the art journal Third Text.

The theme of 2011 in Aarhus Contemporary Art Center, Denmark, is based on his manifesto of Ecoaesthetics from 2009.

Rasheed Araeen and Søren Dahlgaard discuss the farm project Søren Dahlgaard initiated in Maldives from 2002-04 in relation to the manifest and art.

Rasheed Araeen:

There is now a widespread perception in the art world, particularly among those who consider themselves politically engaged and think they can change the world by merely representing its struggles. When they present the images of the struggling world, such as of the struggle in Gaza or the Palestinian land, in art museums, international art fairs or biennales, they think they are producing radical art. This is a delusion created and promoted by the liberal section of the art world, so as to prevent the imagination from penetrating the façade of its charity. As a result, what the so-called politically engaged artists produce is neither significant art nor radical politics.

Charity towards others is an essential part of human emotion and it can enhance one’s concern for those who are in need of help. In the present state of the world, charity does an extremely useful work. I’m all for this charity. But when charity becomes an expression of the paternalism of the powerful, particularly in relation to those who continue to suffer from the legacies of colonialism, then there is a problem.

Although your work is also based on charity, it seems it has managed to avoid the trap of the paternalism I have mentioned above. What I find interesting about your work is the process, which is continuous, and its continuity depends on the efforts and the productivity of the people themselves. You went to the Maldives and initiated an idea there, which was productive and it was then taken up by the people of the Maldives and expanded this idea through their own productivity. Once the people had taken up an idea and carried it forward through their own self-conscious productivity and efforts, it is no longer dependent on the charity that initiated the idea. This is indeed your achievement and I admire what you have done.

However, there remain many unresolved questions. What is art? You say:” it is not important to define the project as an art project or not – it is part of life”. I disagree. I think we will have to define it. How? Maybe our exchange will answer this question.

Søren Dahlgaard:

The vegetable pilot project I did in the Maldives from 2002-04 I was not considering to be a charity project, but perhaps I define charity differently from you? It was a business opportunity I wanted to explore and a lot of good things came out of it.

The main long-term objective was to build a good business my family could make a living from (and it should be an exciting adventure as well). But first I had to test if it was at all possible to grow a number of different vegetables. To do this I had to undertake systematic testing of a large number of crops and crop varieties to identify, which crops would work. I had to develop agriculture in the Maldives almost from zero. All the information and experience gained from these two and a half years of hard work and investment I have given to anyone who wants it. And it is being used in a number of agriculture projects around Maldives today.

Towards the end of the pilot project ADB – Asian Development Bank – wanted a group of experts to write a report titled: Commercialization of Agriculture in the Maldives. This rapport I had just done! So when I was asked to select the team of experts I was able to make use of my newly gained experience and knowledge.

The reason I am reluctant to call it an art project is because the intention and purpose of the project was not to exhibit it and place it in an art context.

This is why I was thinking of myself as a farmer and not an artist during those two years. I moved to a small Maldivian island with my Maldivian wife and child and settled there.

Now 7 years later I am exhibiting the project in an art institution and I want to keep the focus on telling the story and the difference the project has made for the agriculture sector in the Maldives.

I guess what I did also have to do with design. It is about organizing something as essential as fresh fruit and vegetables in a country with practically no land. The Maldives are 300 km2 of land divided on 1200 tiny islands – sandbanks. 1000 island are uninhabited and the islands stretch 800 km from North to South. The capital Malé is the most densely populated capital in the world. Just 2 square km2 housing 150.000 people.

If you can expand your points about art that makes a difference, with reference to your manifesto it would be interesting.

Rasheed Araeen:

I admire what you did in the Maldives, and also appreciate the honesty with which you have presented your work. You did something, which was innovative and was as a result taken up by others and was made the basis of their own productivity. This is an achievement in itself and it doesn’t need to be defined as art in order to be recognized as a socially important intervention. But the matter does not end there, because you are now showing this work in an art gallery as a response I suppose to a manifesto, which was about art. The gallery is in fact presenting your work as a work of art, even against your reluctance to call it art. How do you explain these different views, if not a contradiction?

I know I have raised a very difficult and complicated question, of which I myself do not have an absolute answer or resolution. However, the entry of your work, which was initially conceived and executed as a productive but consumable work or product, into an art gallery must deal with this question. The space of an art gallery must allow us to look at and debate what separates instrumental productivity from the creativity of art. In the manifesto of Ecoaesthetics, I propose to demolish the difference between instrumental productivity and artistic creativity. But this cannot happen within the prevailing order of things, because this difference is fundamental to the bourgeois capitalist society. However, I am not suggesting that it would be possible to get rid of this society merely by an artistic activity and replace it with something radically different, in which the division between productivity of the masses and the artistic activity of socially elevated individuals does not exist. But a radical move can be made through art towards an elimination of this difference or division.

Your work can be a beginning of a continuous process eliminating the division between the productivity of your own work in the Maldives along with the work of the vegetable growers there and what you are presenting in an art gallery in Aarhus, but only when all this is involved together and collectively in questioning and confronting the hierarchy of prevailing things and moves towards what can not only become a unified work of productivity and creativity but also offer a model for reorganizing equitably the whole society.

Søren Dahlgaard: I went about this project in a similar way as when I do my other art projects. First there is a research phase, where I speak with professionals in the specific field to find out about materials, techniques and knowledge. Then there is the pre-production, production and postproduction. Much like a film or theater production, or a small factory production line. This is how I work and there fore I think the agriculture project in the Maldives was similar to my art projects, but just much bigger and over a longer period of time.

By presenting this project in an art institution I want to tell the story of the project. It is a project, which can be of inspiration for people. You can do something, which might seem almost impossible. It can seem like a very adventurous tale, almost as if it is made up and did not happen. But all the evidence is there, pictures of the work and the process. You can even see the buildings on Google Earth as proof.

Art can tell stories and inspire and so can this project inside the art institution.

This project is also a statement as much as other art projects. I saw there was a problem or challenge; the lack of fresh local vegetables in remote areas in the Maldives and it made sense to do something about it. Good business ideas often start like this and so does charity. But can art? I think so. Many art exhibitions are well meaning (theoretical) intentions from well-formulated proposals but the actual outcome is an art opening where the art crowd feels at home but the local community or non art people are either not there or feel alienated towards this strange thing called art. I want to break down the barriers between people and the art institution and make people feel welcome and at ease so they can enter the work. This is one of the reasons I often make use of humor, which serves as an icebreaker to engage in the work.

In this project I think the fundamental challenges about fresh food is something everybody can relate to.

I will make a concert for the plants called Music for Vegetables at the opening, where a classical violin quartet will play beautiful music for the vegetable plants. This is fun and might seem slightly ridiculous to some, but there is serious research proving that plants grow better when they hear music and people are around them.

The myth of talking to your plants, will make them happy, is very known. But there is actually something to it. After we built the residential house in the island of Hibalhidhoo and started living there, the near by coconut trees quickly started to bear more, bigger and tastier coconuts! I told my father in law and he replied; yes off course! Everybody in Maldives knows this!

But how do you prove or even explain this fact? The coconut trees react to the humans being around them by producing nicer and bigger coconuts. They like the company of people!

Rasheed Araeen:

Thank you very much for explaining your project. However, you don’t have to justify your work by merely presenting its physical evidence. It is more than just growing vegetables in the Maldives, as its achievement as art is very much located within a trajectory of art history. In its own right it is a great achievement, and I congratulate you for this extraordinarily courageous work. But when it is looked at as art and within an art historical trajectory, it reveals a significance, which goes beyond what you have described.

When we started this conversation I did not know much about you and the full details of the work. I wasn’t aware of the enormity and complexity of the work. I now know more about your work, also that you were a student at the Slade School of Art in London 1997-2002; and since you describe yourself as a conceptual artist you must have been aware of the Conceptual Art of late 1960s and early 70s. I wonder if this knowledge inspired you in doing what you did, and which way. And what made you go beyond what was then achieved by Conceptual Art as recognized by art institutions? It seems your work does go beyond what has been recognized historically as Conceptual Art, and it should therefore be looked at in its historical trajectory. I will come to this later.

But first let me tell you about something, which you may not be aware. Of course, you wouldn’t know about this because it is not part of art teaching in Britain or history of art taught anywhere in the world. I want to tell you this because the exhibition of your work now seems to be a response — as your gallery has announced — to my manifesto of Ecoaesthetics. Although this manifesto was first launched in London in 2008, its history goes back to the late 1960s when its initial concepts were formed. We are therefore fellow artists pursuing similar things.

There are also other things, perhaps mere incidentals, which seem to connect us. My first attempt to re-articulate the concepts of Land Art (in which I was involved in my own way in the late 1960s in London), the basis of Ecoaesthetics, took place at the end of 1990s. And its first concrete form, in which I put forward the idea of a farming village or community producing its own food as a Conceptual artwork, was presented in Karachi in December 2001. Its second presentation was delivered in the early 2002 at a conference within the premises of the Slade School of Art (when you were then an art student there). Its completed form was published as ‘Towards a Concept of Nominalism’ in Third Text in July-August 2002 (the time when you were completing your studies at the Slade).

These incidentals may not have any significance, and I am not trying to relate your work with them. But they do reveal something significant: a freedom of the idea. As I have pointed out in my text (published as ‘A Journey of the Idea) in my book ART BEYOND ART), an idea can move from one subject to another without they being aware of each other; it can also emerge simultaneously at different places at the same time. So, I am not surprised that when I was formulating the concept of a farming community growing its own food as a work of art, you were actually constructing it with its potential for a continuous growth.

What is more, you have put yourself within the work, thus collapsing the division of subject and object. They have become organically and dynamically one, something the institutionally recognized conceptualism of Land Art could not achieve – as it became trapped within the museum walls.

Let me now return to the historical trajectory of Land or Conceptual Art, to show how your work is a continuation of this trajectory but going beyond its art institutionally and historically recognized boundaries. There were many examples of conceptual works in which land transformation took place. But it was, I think, Robert Morris who first thought of a working farm as a conceptual artwork in 1968. There is however no document showing that he actually went ahead and produced the work. In 1982, almost fourteen years later, Joseph Beuys launched a project, at Documenta in Kassel, for the growing of 7000 trees, which he called a “social sculpture” for “regenerating the life of humankind”. But it didn’t do much for “humankind”, as it was a symbolic gesture within the already established art historical framework of Land Art and became trapped in it.

What is therefore remarkable about your work is that while it is located historically within this framework, it breaks its art institutionally contained boundaries and enters into a life’s process. However, although your work has entered the life of an organic process and given it something that is life enhancing, it is difficult to predict its further movement. Whether it is going to stay where it is today, going into cyclic movements and reproducing them in celebration of its achievement, or can move further beyond an achievement of its individual subject, is difficult to say.

Your work’s achievement should however be recognized in its own terms, which is enormous, without considering it as an outcome of the manifesto of Ecoaesthetics. Although the work has some elements of the manifesto, it has not yet moved to a point where it can be fully considered a manifestation of its fundamental concept of an egalitarian farming collective or community. It is difficult for me to say now whether you want to go further, so that the work becomes the work of a community rather than of an individual as being shown now in the gallery; nor I want to suggest that you should necessarily follow the path of the manifesto. The choice should be entirely yours, though we can discuss this when we meet.

There is something important which I want to take up. It is about the transformation — which is fundamental to your work — in relation to representation, particularly when representation becomes an object representing transformation outside its own context or space (a gallery or museum); which actually leads to a contradiction whose resolution is not found within the regime that demands the primacy of representation as the ultimate goal of art. However, I am not thinking only of your work but also about my own propositions that are part of Ecoaesthetics and other texts included my book mentioned before, with a question that cannot be resolved within the context of representation even when it is through representation that a transformation becomes a work of art. The solution to this seems to be a conciliation of the two through a transitory space between now and what the future holds in terms of their eventual disentanglement. However, it is not my intention here to drag you into this extremely difficult problem, which may not be necessary to invoke at this stage of your work. But a discussion of this problem may highlight what your work may face when it is appropriated and legitimized as a work of art merely by a representation.